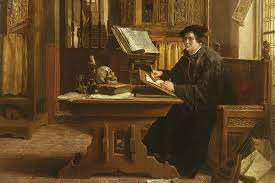

Martin Luther (1483-1546), a 16th-century monk and theologian, was one of the most significant figures in Christian history. His beliefs helped birth the Reformation—which would give rise to Protestantism as the third major force within Christendom, alongside Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

The early life of Martin Luther

Martin Luther was born in 1483 to Hans and Margarethe Luder (later Luther) in Eisleben, Germany. His father was a hard-working leaseholder of copper mines and smelters, who was determined to see his son become a lawyer. So, he first sent Martin to a Latin school in nearby Mansfield, then to Magdeburg, and after that to Eisenach. All three schools focused on grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory and hell.

He entered the University of Erfurt in 1501 at the age of seventeen, where he received his master’s degree in 1505. Though he enrolled in law, he dropped out of it almost immediately, much to the dismay of his father. When two of his friends died, he became more interested in religion. He believed law represented uncertainty, and he was drawn to theology and philosophy because he sought assurances about life.

Philosophy also became unsatisfying to Luther because it could not lead to a knowledge of God. Luther believed that philosophy might give assurances about the use of reason, but God could only be known through divine revelation. Therefore, Scripture became increasingly more important to him.

Luther’s formation into a preacher and theologian

The storm that changes Luther’s life

On July 2, 1505, as Luther was on his way back to the University, his life was about to change dramatically. He was caught in a fierce thunderstorm. So, he took shelter from the torrential downpour under an elm tree, and a lightening bolt split the tree above him. In a state of terror, he desperately cried out to who he thought was the patron saint of miners, “St. Anne, save me and I will give up my studies…I will even become a monk!”

Afterward, when his friends questioned him about his decision to quit his legal education and become a monk, he explained that he had taken a vow and therefore could not break it.

Becoming an Augustinian monk

Luther broke the news to his father that he had decided to join the monastery by writing him a short letter after he had already been admitted. Eventually, his father resigned himself to Martin’s decision, “with reluctance and sadness.”

The monastery that Martin joined in 1505 was of the Augustinian order in Erfurt. It was one of thirty monsteries of that order in Germany at that time. Martin was first admitted into the order as a novice. As a brilliant student, Luther was a marked man. He was given the most menial tasks to perform, including begging on the street. The life of a monk was also very demanding. At the end of his one-year probationary period, Luther took his lifetime vow of loyalty to the order and to God. And he became a full-fledged lay member of his monastic community.

Throughout his time in Erfurt, Luther was stricken over the guilt of his sin. He would regularly spend hours in confession as he sought to clear his conscience of everything that could possibly offend God. Yet, he despaired of what would come of himself when he died, for he was terrified at the prospect of facing almighty God. Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinian order, told Brother Martin to remember not to dwell on how much he must pay to satisfy his guilt, but how much Jesus paid for him.

Becoming a priest

Knowing Luther’s talent as a student before entering the monastery, Staupitz selected Luther to become a priest. So, Luther returned to Erfurt University to study theology, where he earned a bachelor of arts degree in the Bible and then became a priest. But Luther’s perceived sins continued to haunt him. It was as if Luther was trying to earn his way to heaven, instead of accepting God’s pardon and forgiveness.

“I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul.”

Martin Luther

Luther transferred to the Augustinian monastery at Wittenberg in the fall of 1508 and continued his studies at the university there. After only a year of study, Luther had completed the requirements not only for the baccalaureate in Bible but also for the next-higher theological degree, that of Sententiarius, which would qualify him to teach Peter Lombard’s Four Books of Sentences, the standard theological textbook of the time.

The trip to Rome that gives Luther doubts about the church

In 1510, Luther became disillusioned over the condition of the Catholic Church when his superiors sent him to Rome to help settle a dispute among monasteries. On the way down, he was annoyed at the extravagance of the monks. And when he arrived in Rome, he saw how dirty and violent it was. Cardinals were living in open sin with their mistresses. Luther was horrified to see how cavalier the priests were in performing the mass. They seemed to be competing with each other to see who could complete the most masses in a single hour. And the Pope was too busy raising money and fighting a war with France to trouble himself with Luther’s matter.

Nevertheless, Luther tried to make the most of his trip. He ascended the twenty-eight steps of the sacred stairs at the Lateran Church on his hands and knees. (The stairs are a relic that’s thought to be the same stairs Jesus Christ climbed when he was presented for judgment before Pilate.) He said the Lord’s Prayer and kissed each step all the way to the top. Some people believed a soul would be released from puratory every time a prayer was said. In a strange sort of way, Luther almost wished his parents were dead so that his prayers would have benefited them. When he got to the top of the stairs, he stood up and said, “who knows whether it is true?”

Luther becomes a theologian

Upon completion of his studies at the University of Wittenberg in 1512, Luther was awarded his Doctor of Theology. He was then admitted into the theological faculty of the University, where he spent the rest of his career.

In 1515, Luther was made the provincial vicar of Saxony and Thurinigia, which meant he would visit and oversee each of eleven monasteries in his province.

Disputes over Roman Catholic beliefs

Luther nails his 95 theses to the door of the Church in Wittenberg

In 1516, the Roman Catholic Church sent Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar to Germany to raise money to rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Rome had agreed to offer indulgences to eliminate or reduce the time deceased loved ones would have to spend in pergatory. Tetzel brashly went through Germany selling these indulgences to anyone willing to buy them. This abuse of the penitential sacrament of the church greatly disturbed Luther.

So, Luther wrote a letter to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting against the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his “Disputation on the “Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”, which came to be known as the Ninety-five Theses. (Luther was long believed to have posted the theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, though scholars remain divided on this.) The Bishop later said that Luther had no intention of confronting the church but saw his dispute as a scholarly objection to church practice.

In 1517, the Theses, which were written in Latin, were printed in several locations in Germany. And in January 1518, friends of Luther translated the Theses from Latin into German. Within two weeks copies of these had spread throughout Germany. The act which Luther had intended to be a quiet debate among other theologians suddenly placed him squarely in the limelight of the German people.

The breakthrough that led to Luther feeling reborn

Understanding what Paul meant by “the righteousness of God”

During his teaching time at the University of Wittenberg, Luther studied the Psalms, Romans, Galatians, and Hebrews. While he was studying the first chapter of Romans, he ran across a statement by Augustine related to Romans 1:17 “For therein is the righteousness of God revealed from faith, to faith: as it is written: ‘The just shall live by faith.'”

Luther came to one of his most important understandings: that the “righteousness of God” was not God’s active, harsh, punishing wrath demanding that a person keep God’s law perfectly in order to be saved. Rather, Luther came to believe that God’s righteousness is something that God gives to a person as a gift, freely, through Christ. Luther previously thought he had to work for it, earn it, and so he earnestly strived after it. But now he realized he couldn’t do it. It’s outside of us. It’s a righteousness that is applied to us. This was the breakthrough for Luther. Once that happened, everything began to unfold.

Experiencing the liberating freedom of God’s gift of righteousness by faith

Later in life, Luther wrote about his conversion experience, which most likely happened in the early months of 1519.

I gave heed to the context of the words, namely, “In it the righteousness of God is revealed, as it is written, ‘He who through faith is righteous shall live.’” There I began to understand that the righteousness of God is that by which the righteous lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. And this is the meaning: the righteousness of God is revealed by the gospel, namely, the passive righteousness with which merciful God justifies us by faith, as it is written, “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates. There a totally other face of the entire Scripture showed itself to me.

Martin Luther

Debates in Augsburg and Leipzig

The Elector Frederick persuaded Pope Leo X to have Luther examined at Augsburg, instead of being called to Rome, where the Imperial Diet (assembly) was held. At the 1518 Diet, Cardinal Cajetan questioned Luther about the pope’s right to issue indulgences. The hearings degenerated into a shouting match, and the confrontation cast Luther as an enemy of the pope. He said that the pope abuses Scripture and denied that he is above Scripture. Cajetan’s instructions were to arrest Luther if he refused to recant, but Luther slipped out of city at night, without Cajetan’s knowledge.

In 1519, Andreas Karlstadt, the dean of the Wittenberg theological faculty, felt that he needed to defend Luther against Johann Eck‘s critical commentary on the 95 Theses. So, Karlstadt challenged Eck to a public debate in Leipzig about the doctrines of free will and grace. Eck, who was considered the master debater, invited Luther to join the debate. Luther and Eck expanded the debate to include other matters, such as the existence of purgatory, the sale of indulgences, the need and method of penance, and the legitimacy of papal authority.

Luther’s boldest assertion in the debate was that Matthew 16:18-19 does not confer on popes the exclusive right to interpret Scriptures, and therefore neither popes nor church councils were infallible. This caused Eck to brand Luther as a new Jan Hus, the heretic who was burned at the stake in 1415.

Luther’s break with Rome

Luther writes three critical treatises

Three of Luther’s best know works were published in 1520. They included To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian.

On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, published in October 1520, encapsulated Luther’s ideas for theological reform. This treatise, rejected four of the seven traditional sacraments, preserving only Baptism, Eucharist, and Penance.

In the “Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,” Luther attacked the corruptions of the Church and the abuses of its authority, and asserted the right of the layman to spiritual independence.

In his treatise On the Freedom of a Christian, Luther developed the concept that as fully forgiven children of God, Christians are no longer compelled to keep God’s law to obtain salvation; however, they freely and willingly serve God and their neighbors. Luther also further develops the concept of justification by faith.

Pope Leo X lashes back

On June 15, 1520, the Pope issued a papal bull (decree) that charged Luther with 41 instances of deviation from the teaching and practice of the church and ordered him to recant them, along with the Ninety-five Theses within 60 days or suffer excommunication.

In response to the papal bull, Luther publicly set fire to the bull at Wittenburg on December 10, 2020. By burning these works, Luther signaled his decisive break from Catholicism’s traditions and institutions. Consequently, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X on January 3, 1521. And the Catholic Church has never lifted the 1521 excommunication.

The showdown at the Diet of Worms

While the Emperor Charles V should have arrested and executed Luther due to his excommunication, Frederick the Wise of Saxony intervened and the decision was made that Luther would be summoned for a hearing at the Diet under the emperor’s promise of safe-conduct.

On April 17, 1521, Luther came before the Diet. Johann Eck presented Luther with copies of his writings laid out on a table and asked him if the books were his and whether he stood by their contents. Though Luther confirmed they were his, he requested time to think about his answer to the second question.

After much soul searching and prayer, he gave his responses the next day:

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.

Martin Luther, at the Diet of Worms

On May 25, 1521, the Edict of Worms was issued. It declared Luther to be an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest. It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. And it permitted anyone to kill him without any legal consequence.

Luther is “abducted” and goes into hiding

Luther’s disappearance during his return to Wittenburg was planned by his protector, Fredrick III. He had masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers intercept Luther and take him to the security of Wartburg Castle at Eisenach. He was hidden there from public sight for eight months, during which time he translated the Bible into German. Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522.

Luther saw that God had used him as a mouthpiece for the truth. Later, he declared the power of God’s Word:

“I simply taught, preached, and wrote God’s Word; otherwise I did nothing. And while I slept … the Word so greatly weakened the papacy that no prince or emperor ever inflicted such losses upon it. I did nothing; the Word did everything.”

Luther, explaining the Reformation’s success on March 10, 1522

The beginning of a reformed Christian church

Luther Guides the establishment of churches based on Lutheran beliefs

Upon his return to Wittenberg, Luther preached the “Invocavit Sermons“, a series of eight short sermons in which he taught the people of Wittenberg how the reformation of the Church should be carried out. It must be based on God’s clear Word and it must care for the conscience of the Christian. In these sermons, he stressed the Christian values of love, patience, charity, and freedom. And he reminded the people to trust God’s Word rather than violence to bring about needed change.

Luther’s choice to spread reform non-violently

Luther next began reversing or modifying the new church practices. He worked alongside the authorities to restore public order. However, he battled against both the established Church and the radical reformers who threatened the new order by fomenting social unrest and violence. Revolts by the peasantry broke out in places outside Wittenberg, which included widespread burning of convents, monasteries, bishop’s palaces, and libraries.

Though Luther sympathized with some of the peasants’ grievances, he reminded them to obey the temporal authorities, based on Scripture (Matthew 22:21, Romans 13:1-7). Without the backing of Luther, many rebels laid down their weapons, while others felt betrayed. The revolutionary state of the Reformation came to a close. Only late in life did he develop the Beerwolf concept, which permitted some cases of violence against the government.

The marriage and family life of Luther

Luther married Katherine von Bora in 1525. Katherine was an ex-nun committed to the Reformation cause. Luther’s family life was a very happy one. Their union gave birth to six children. And their home was a place of busy activity, with their children, nephews, nieces, and orphans. They also opened their home to vistors and travelers, which also added to the chaos.

By 1528, the Reformation had swept through Germany. And through his writings, Luther’s influence expanded to surrounding countries. Students from all over Europe came to learn from this great Reformer.

Luther debates Ulrich Zwingly, the Swiss reformer, in Marburg

In 1529, the Marburg Colloquy was set up to resolve a major disagreement between the German and Swiss reformers over the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. Luther believed that the substance of the bread and wine coexists with the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. However, Ulrich Zwingly, the Swiss reformer, believed that the elements are simply a memorial of Christ’s body and blood. The two men could not reach an agreement. Unfortunately, Luther left without the issue being resolved.

The drafts of articles that describe Lutheran beliefs and practices

The Augsburg Confession. In 1530, Luther’s friend Philipp Milanchthon wrote the 28 articles that constitue the basic confession of the Lutheran Churches. The purpose was to defend the Lutherans against misrepresentations and to provide a statement of their theology that would be acceptable to the Roman Catholics. The Catholic theologians, however, replied with the Confutation, which condemned 13 articles of the Confession, accepted 9 without qualifications, and approved 6 with qualifications. The emperor refused to receive a Lutheran counter-reply.

The Schmalkaldic Articles. In 1536, articles were prepared by Martin Luther as the result of a bull issued by Pope Paul III calling for a general council of the Roman Catholic Church to deal with the Reformation movement. (The council was actually postponed several times until it met in Trent in 1545.) The articles represent a summary of Lutheran doctrine, prepared for a meeting of the Schmalkaldic League in preparation for an intended ecumenical Council of the Church.

The theology of Martin Luther was instrumental in influencing the Protestant Reformation, specifically topics dealing with justification by faith, the relationship between the law and gospel (also an instrumental component of Reformed theology), and various other theological ideas. Although Luther never wrote a systematic theology or a “summa” in the style of St. Thomas Aquinas, many of his ideas were systematized in the Lutheran Confessions.

Luther’s final years

Up until the end of his life, Luther maintained a heavy schedule of lecturing, preaching, teaching, writing, and debating. He became weaker as this took its toll on him, and he became subject to various illnesses. In 1537, he was so ill that his friends thought he would die. In 1541, he again became seriously ill and Luther himself thought he was about to die. Yet, he recovered once again. Finally, he was on his way to Mansfield, following the preaching he had done in his hometown of Eisleben. That evening, surrounded by three of his sons and some friends, he died in the early hours of February 18, 1546.

Martin Luther’s legacy

Luther’s ideas had a profound impact on the church and on Western society as a whole. His challenge to the authority of the Roman Catholic Church led to the Protestant Reformation, which was a major split in the Christian church. The Protestant Reformation gave rise to many new denominations of Christianity, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anglicanism. Earlier reformers attempted to bring reforms to the established church. But Luther knew that real reformation could only come by totally separating itself from the Roman Catholic Church.

Martin Luther became one of Western history’s most significant figures. He believed, preached, and taught two central beliefs—that the Bible is the central religious authority and that humans may reach salvation only by their faith and not by their deed. This monumental departure from the established church’s teaching sparked the Protestant Reformation.

Although these ideas had been advanced before, Martin Luther codified them at a moment in history ripe for religious reformation. The Catholic Church was ever after divided, and the Protestantism that soon emerged was shaped by Luther’s ideas. His writings changed the course of religious and cultural history in the West. Protestants now account for nearly forty percent of Christians worldwide and more than one tenth of the total human population

Luther’s emphasis on the importance of the individual’s relationship with God had a significant impact on the development of Western thought. His rejection of the authority of the church paved the way for the development of modern secularism and individualism.

Reflections on Luther’s life

Our relationship with God begins with an awareness of the uncertainty of life

When we’re just as concerned with the life hereafter as we are with our lives now, we’ll strive to learn what only God can reveal.

Luther had mourned the loss of two of his friends whose lives were cut short. This experience awakened him to the fragility of life. Then, Martin Luther was pursuing a legal career when God got his attention through the fierce thunderstorm that could have taken his life. He was shaken up to the point that he realized he wasn’t ready to meet his Maker. So, this matter became more important to him than the course he was on, and he made a vow to become a monk.

The fear of God is the beginning of wisdom

The fear of unresolved guilt and godly sorrow drives us to search for a satisfactory solution to our unworthiness before a perfect, holy, and just Creator God.

Luther had a keen legal mind. So, it was natural for him to recognize his own failures to keep God’s law. This haunted him and made him want to try harder and harder. The more he tried, however, the more frustrated he became. When Luther thought about God’s holiness and His requirement that His children be holy, he said, “Love God? Sometimes I hate Him!” Nevertheless, Luther pursued holiness all the same.

Love for God is based on a confident assurance of what God has done for us

As long as we trust in ourselves to attain to the righteousness God requires from us, we’ll be uncertain about our standing with Him. But when we trust in God’s promise that He’ll do all that is required, we can rest assured that He loves us, and that assurance leads us to loving and following Him.

Luther’s conversion to Christ came well after the time he became a priest. Before he was converted, he viewed Christ as the One who would give him the severe justice he knew he deserved. But at his conversion, he saw Christ much differently. It was Christ who was freely giving Martin all the righteousness that he couldn’t attain on his own. His salvation no longer depended on his perfect law-keeping, which he knew he couldn’t do. Now, Jesus became for him a precious Savior and the Lord he would always seek to please.

Genuine faith is a gift from God that perseveres to the very end

True faith in God can only come from God as a free gift from Him, and His gifts are irrevocable. We did nothing to deserve that gift, and consequently, we cannot do anything to lose it.

Luther’s faith was tested time after time. It persevered through debates with Cardinal Cajetan and Johann Eck. It also survived through the threat of excommunication and the death sentence placed on him at the Diet of Worms. He was more concerned with being faithful to the Word of God than pandering to the desires of sinful men. His perseverance was due to God’s promise and power to preserve His people to the very end.

Christians become like shining stars in the universe that either attract or repel others

Light seeks greater light, and darkness flees from the light. Therefore, Spirit-filled Christians attract others who are being saved, but repel those who reject God’s way of reconciling sinners to Himself.

The spiritual life of the Roman Catholic Church was nearly snuffed out by the time Luther came on the scene. The sacramental system was conceived by popes and church councils to control its adherents by offering them a supposed way of salvation that is dependent on its clergy. For the lay people, it gave them a way that could ensure them of their salvation, if only they fully follow the system.

When Luther taught that the Bible teaches justification is by faith alone in Christ alone, he threatened the authority and supremacy of the church. He became their enemy and they sought to kill him. But countless others during and after Luther’s time have embraced the truth that he taught and have become the true children of God.

Taking a stand for what is true

Genuine saving faith places the Person and work of Jesus Christ as its main object. The Bible gives us the details of His life in the four gospels, and the epistles help to interpret the meaning of His life. To interpret Jesus’ life and mission in a way contrary to Scripture is to deny Him. For example, if we deny His divinity, we reject Him. And if we deny His humanity, we also reject Him.

But as important as it is to believe in the biblical Jesus, it is just as important to know how we can apply the benefits He has to offer to our own lives. To illustrate, if we rely on anything to merit God’s mercy and grace, other than faith in Christ as our Savior and Lord, we miss receiving it. Even the faith that saves is not our own; it is a gift of God. Therefore, God has made certain that He alone will receive credit for our salvation. Though that goes contrary to our natural desire to control our own lives, it is the road to loving God with all our heart, soul, mind, and spirit.

These truths are worth living for and dying for, because they lead to forgiveness of sins and eternal life. Otherwise, we are condemned to eternal destruction. If you want to know more about God and our salvation, visit my blog How to Begin Your Life Over Again. And click here to view some excellent YouTube gospel presentations. Seek Him with all your heart and you will find Him (Jeremiah 29:13).

Sources

Steven J. Lawson. Pillars of Grace: AD 100 – 1564. Ligonier Ministries, Sanford, FL. 2011, pp. 331-361.

Sinclair B. Ferguson, In the Year of our Lord: Reflections on Twenty Centuries of Church History. Ligonier Ministries, Sanford, FL. 2018. pp. 161-169

Mike Fearon. Martin Luther. Bethany House Publishers. Minneapolis, MN. 1986.

A. Kenneth Curtis, J. Stephen Lang, Randy Petersen. The 100 Most Important Events in Christian History. Fleming H. Revell (Baker Book House), Grand Rapids, MI. Original work published 1991, pp. 96-98.

Martin Luther. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Luther

Selected events in Martin Luther’s life. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://speccol.library.arizona.edu/online-exhibits/items/show/1379

The Diet of 1518. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diet_of_Augsburg#:~:text=5%20Notes-,The%20Diet%20of%201518,the%20throne%2C%20but%20he%20failed.

Leipzig Debate. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leipzig_Debate

Diet of Worms. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/print/article/649151