Gottschalk was born in Saxony in the northern part of Germany. He joined the Benedictine Order as boy, a decision that troubled him later in life. Gottschalk became a controversial figure when his teaching on the Augustinian doctrine of predestination provoked sharp negative reaction. He was branded a heretic and forced to throw his books in the fire, publicly flogged, deprived of his priesthood, and effectively imprisoned and condemned to perpetual silence. Gottschalk stood courageously for the absolute necessity of God’s sovereign grace in our salvation.

Gottschalk’s early life

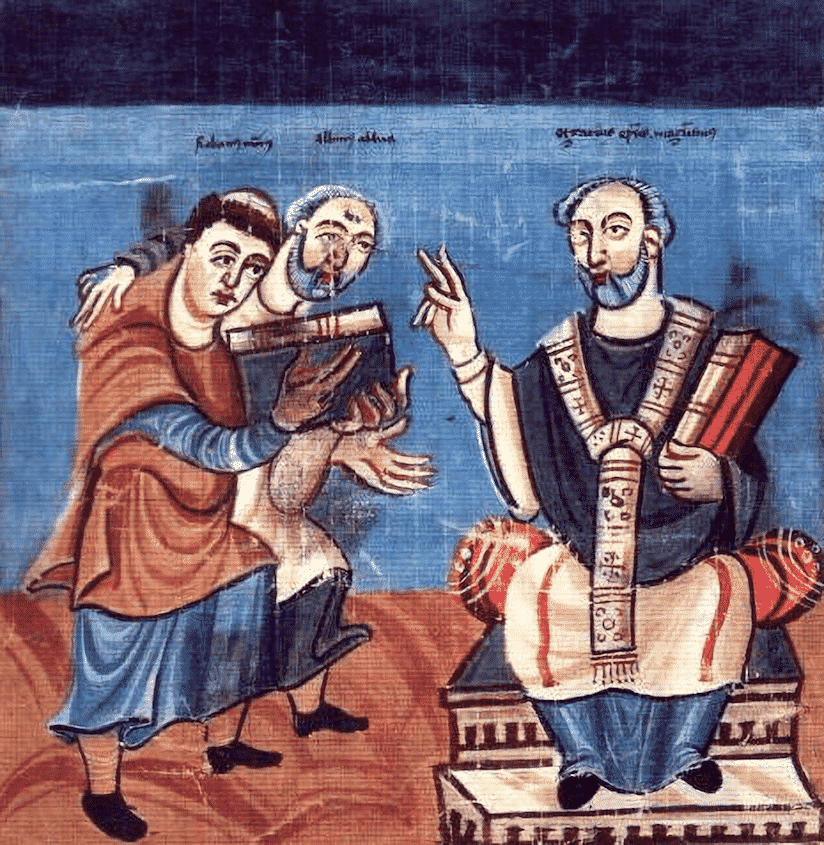

Gottschalk was born of noble birth. His parents dedicated him to monastic life when he was just a child. But Gottschalk requested release from his monastic obligations. And at the Synod at Mainz in 829, when he was about twenty-six, his request was granted. By challenging the practice of coerced admission of children in monasteries, usually on the request of families, Gottschalk turned his superior, Rabanus Maurus, into a life long enemy.

Released from his vows, the young man set out for a journey. He spent some time at the monastery of Corbie in Picardy. At Corbie, Gottschalk was trained as a missionary. He also met well-respected theologians like Ratramnus, with whom he would later correspond.

Rabanus then demanded Louis I the Pious, the Carolingian emperor, to force Gottschalk back into monastic life. He became a monk again and settled at the monastery of Orbais, France.

Gottschalk’s missionary preaching

While few medieval Christians would profess to disagree with Augustine of Hippo, including his writings about grace, many praised him and contradicted him at the same time. Copyists were partly to blame. Due to the price of hand-copied books, they often chose to produce collections of quotations that others took to be authoritative. However, sometimes the quotations were taken out of context, often misquoted, and sometimes attributed to the wrong person. For example, a work by Pelagius was wrongly entitled Sermon of Augustine.

By this time, however, kings and scholars were giving greater attention to details about God’s grace, including predestination, free will, and the extent of the atonement. Gottschalk was concerned with how and why God saved sinful human beings. He argued that those who were saved were such ‘through gratuitous benefit of God’s grace alone’, whereas the damned were such ‘through the most just judgement of God’s immutable justice’.

Gottschalk had been preaching in the eastern region of the Alps, in today’s Croatia and Bulgaria. His emphasis was on God’s sovereignty and on the absolute necessity of God’s grace in salvation.

One of his listeners, however, told Rabanus, who was then the bishop of Maize, that Gottschalk was teaching that God determines the eternal destiny of both the elect and the reprobate. And he was reported to have said that nobody could do anything about it except maybe pray for a milder sentence in hell. Although it is doubtful Gottschalk ever phrased his teaching this way, he decided to meet Rabanus at the synod in order to clarify his views.

The controversy at the Synods of Maize and Quierzy

Gottschalk’s views were condemned at the Synod of Maize in 848, in spite of the fact that his teachings coincided with those of Augustine and other well-respected theologians. The bishops had him flogged for heresy. He was also forced to swear he would never preach again in the eastern Frankish kingdom. He was then placed under the custody of Bishop Hincmar of Reims, in the same region where he had become monk.

Nonetheless, Gottschalk didn’t lose hope since he still had several supporters in his previous monastery and at Corbie. He believed he would be vindicated at the upcoming Synod of Quierzy. However Hincmar remembered him as being rebellious and condemned him again. This time, Gottschalk was excommunicated, beaten almost to death, and forced to burn some of his writings. He was also kept confined in forced silence at the monastery at Hautvillers.

These punishments, however, did not stop Gottschalk from producing new writings and corresponding with friends outside the walls. A group of young monks smuggled his papers and provided him with books and writing materials. Hincmar complained that Gottschalk was a demonic agent, who was corrupting the monastery’s youth. Not only was Hincmar convinced that Gottschalk was dangerous, he also judged him to be insane, due to his frequent odd behavior.

Failed attempts to appeal to the Pope

In 863, Gottschalk appealed to Pope Nicholas for justice. Although Nicholas summoned a meeting at Metz where Hincmar and Gottschalk could explain their views, the meeting never took place. Hincmar refused to attend and Gottschalk became gravely ill.

In 866, another monk secretly went to Rome to bring Gottschalk’s writings to Pope Nicholas, who was known for his Augustinian leanings. But by this time, the Pope had other serious matters on his mind, and this meeting never took place.

Near the time of Gottschalk’s death, Archbishop Hincmar gave him one last opportunity to recant. When he refused, he ordered that he be buried as an unbeliever, outside consecrated grounds and without the sacraments.

Gottschalk’s lasting impact

For a long time, it seemed that Gottschalk’s views came to an end. In 860, the Synod of Tusey agreed with Hincmar that free will was not lost after the fall, but cooperated with grace in order to obtain a salvation that Christ had made possible to all. While they agreed that some were predestined for salvation, they based it upon God’s foreknowledge of man’s will rather than by divine decree. They made no mention of the reprobate. Thus, the views of Pelagius prevailed.

Gottschalk’s writings remained fairly unknown until 1631, when James Ussher, an Irish archbishop, published his Confessions. He believed that Gottschalk was a prototype Protestant. His views share most similarities with John Calvin. Calvinist historians, such as Ussher, also sided with Gottschalk for his predestinarian views.

It’s instructive to consider the parallels between the doctrinal debates of the Reformation and those in earlier centuries. A parallel can be drawn between Gottschalk’s language of salvation by ‘grace alone’ and Luther’s teaching of ‘faith alone.’ While much focus is given to Luther and his future impact, we should not neglect his connections with what came before him.

Reflections of Gottschalk’s life

Upholding foundational doctrines of Christian faith are worth the fight

What we believe in our heart determines our eternal destiny. For Christians, it can also alter our sense of security and love for the Lord. Consequently, Christian maturity for ourselves and others depends on knowing and trusting in the ‘hard’ truths of God’s Word.

There was much confusion and interest in the ninth century about matters of God’s grace. What was God’s role in electing those to be saved? What was man’s role? Was election based on God foreknowing the will of some or all of those ‘destined’ for salvation? These and other similar questions were being asked by those who held influence on others.

The apostle Paul dealt with an issue like this when he rebuked the Galatians for believing they had to first become Jews before they could come to Christ. Paul called the teaching damnable. He said they were believing a gospel that is not a gospel. (See Galatians 1:6-8.) The same can be said of those who believe their eternal fate, in part or in whole, depends on their own righteousness in the final analysis.

Biblical truths that easily promotes sharp negative reactions should be taught with a pastoral spirit that seeks to avoid needless hostility

Handling potentially divisive matters with special prudence and care may assure others of their eternal salvation while still preserving unity.

Gottschalk’s views may have been expressed sharply to others who were already predisposed to competing viewpoints. At the Synod of Maize in 848, he apparently provoked the condemnation of Bishop Hincmar, whom he had previously undermined at the synod in 829. While a more gentle spirit may not have changed the outcome of the debate, it could have favorably altered its consequences.

Men who stand courageously for God’s Word in spite of suffering deserves to be honored.

Christians are called to unity. But true unity among believers is based on common agreement about the essential truths of biblical faith. This would include the nature of God, the nature of man, and how sinners can be reconciled with a holy and just God.

Our enemy, the devil, seeks to divide and destroy believers in Christ. He sometimes uses unbelievers to infiltrate the church and attempt to destroy it from the inside. When that fails, he often results to persecuting those who are willing to fight for the truth and the unity of those who follow it.

Gottschalk loved the truth, which was first spoken by the apostle Paul and then later taught by Augustine. This doctrine was so precious to him that he was willing to undergo great punishment and suffering for it. But, he was not willing to be silenced, and he refused to disavow his firmly-held beliefs. Such lovers of the truth deserve to be remembered and honored. God honored Gottschalk by uncovering some of his writings after seven hundred years of obscurity. Now, we see that his understanding of God’s Word parallels that of Luther’s, who is regarded as the great church reformer.

On whom do you trust for eternal life?

Eternal salvation is based on belief in the Person and work of Jesus Christ, God’s only Son (John 3:16, Romans 10:9-10). We cannot work for it and we cannot merit it (Ephesians 2:4-5, 8-9). Salvation does not depend on man’s effort or desire, but on God’s mercy (Romans 9:14-16). Anyone who relies on observing the law of God for salvation is sure to be cursed (Galatians 3:9-14).

If you are unsure whether you’re saved or not, consider what you would say if God asked you why He should allow you into His heaven. If your answer would include anything other than what His Son has done for you, then I believe you are in danger of going to hell for eternity. For more information about God and why you should believe in Jesus Christ, visit my blog at “How to begin your life over again.” And click here, if you would like to view a few very good YouTube presentations of the Gospel.

Sources:

Book Sources:

Sinclair B. Ferguson. In the Year of our Lord: Reflection on Twenty Centuries of Church History. Ligonier Ministries, Sanford, FL. 2018. pages 93-95, 99-102.

Online Sources:

Gottschalk of Orbais – Bold Witness and Sweet Poet. https://www.placefortruth.org/blog/gottschalk-orbais-%E2%80%93-bold-witness-and-sweet-poet

Reformation parallels: the case of Gottschalk of Orbais – https://doinghistoryinpublic.org/2017/07/18/reformation-parallels-the-case-of-gottschalk-of-orbais/

Gottschalk of Orbais, https://en.wikipedia/wiki/Gottschalk_of_Orbais

Gottschalk of Orbais, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gottschalk-of-Orbais